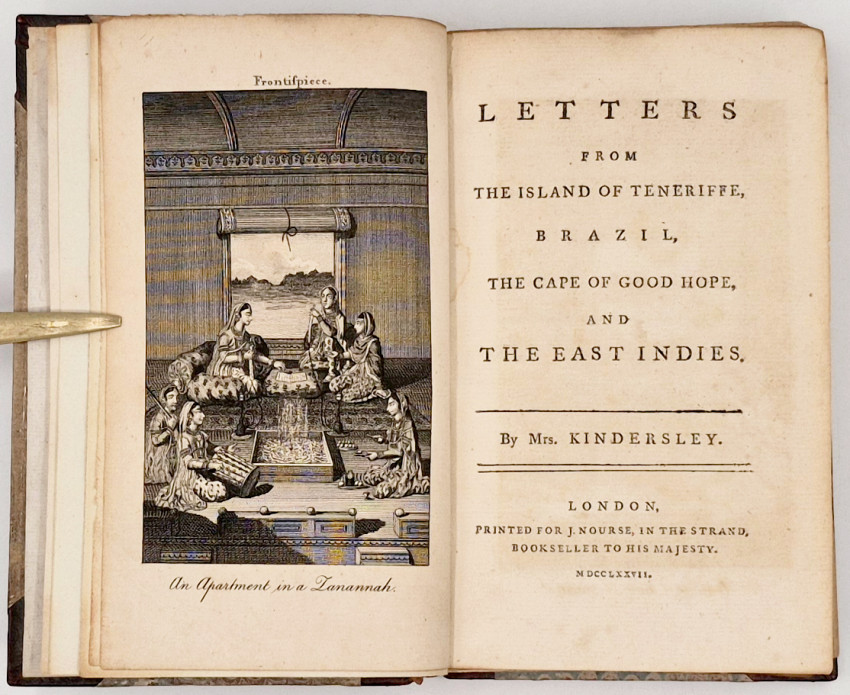

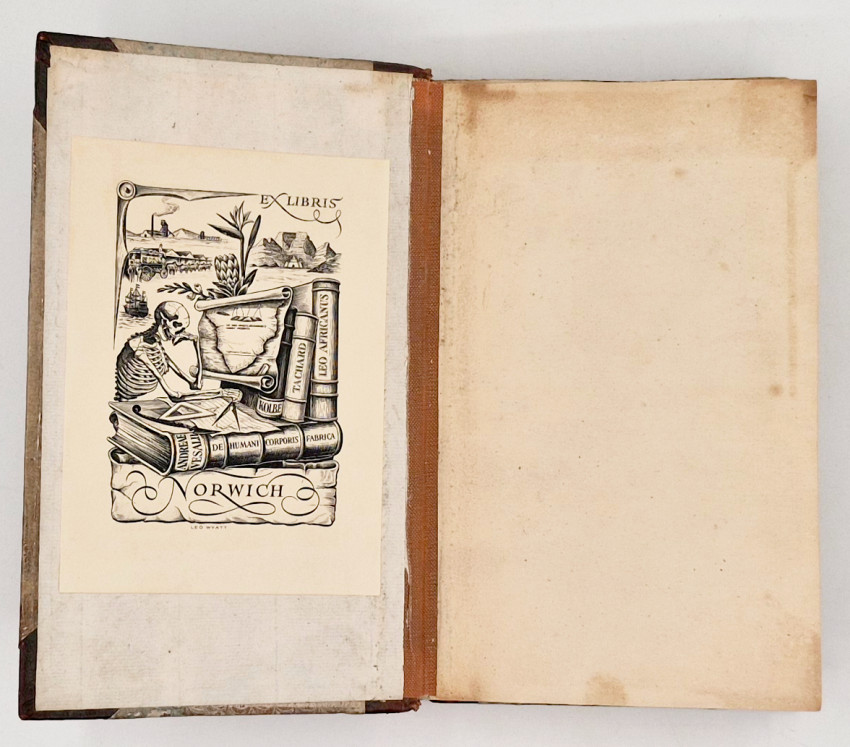

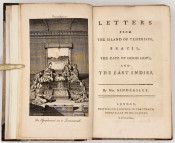

First Edition: 301, (i errata), pages, engraved frontispiece, simply bound in half brown leather and marbled paper sides which are worn and dull, hinges reinforced with brown cloth, book plate on the front paste-down endpaper, a very good copy.

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/45854): 'Kindersley [née Wicksteed], Jemima (1741–1809), travel writer, was born into the modest Wicksteed family on 2 October 1741 in Great Yarmouth, Norfolk, where on 19 April 1762 she married Lieutenant Nathaniel Kindersley (1732–1769) of the Royal Artillery. They met at a local ball, where he was doubtless struck by her beauty, for she became known as Pulcherrima. Their only son, Nathaniel (1763–1831), was born on 2 February 1763.

'In 1764 Kindersley transferred as captain to the East India Company's Bengal artillery, and sailed for Calcutta with his wife and son. Despite her humble background and initial lack of education, Jemima Kindersley responded to the opportunities of her elevation in society. She acquired a fluent prose style, a knowledge of French, and an acquaintance with the ideas of leading philosophers such as Montesquieu, and historians of South America and Asia, which enabled her to write a confident account of her journey to India and life there, mainly in Calcutta and Allahabad, from 1764 to 1768, Letters from the Island of Tenerife, Brazil, the Cape of Good Hope and the East Indies. Her work gives an interesting account of the early period of British consolidation in north India. It is also important as one of the first travel books by a woman, a field in which there were soon to be many female contributors.

'The Letters, which contain no personal information and omit her shipwreck in Bengal, record her wide-ranging observations of local life, religion, and culture, and consider more generally the prevailing characteristics of Indian society. She approached India within the framework of Enlightenment thought and concerns elaborated particularly by Montesquieu, believing that climate shaped character, and that presumed 'oriental despotism' undermined politics, society, and military achievement, and controlled the lives of Indian women. She was particularly interested in the latter, and sought to investigate suttee. As a woman she was able to visit a zenana in Allahabad, and gives one of the earliest Western accounts of the appearance and life of Muslim women. Her careful description avoids over dramatization, but stresses the restrictions imposed on them.

'Jemima Kindersley returned to England with her son in 1769 because of ill health, and her husband died in Calcutta the same year. The Letters were published in 1777, possibly to earn money, since she was left with only a small pension, from which she helped support her mother. Her work met with a warm response; several periodical journals published excerpts, while the Monthly Review, though noting that much of her information was not new, praised the narration of 'a variety of amusing particulars with much ease and simplicity, and with every mark of fidelity' (57, 1777, 243). She thus helped set the pattern for women travel writers, who were welcomed for their style and ability to popularize subject-matter which was often dry or difficult of access.'

Mendelssohn (Sidney) South African Bibliography, volume I, pages 826/7, Pages 52/72, contain an account of the Cape.

- Overall Condition: Very good

- Size: 8vo (180 x 110 mm)