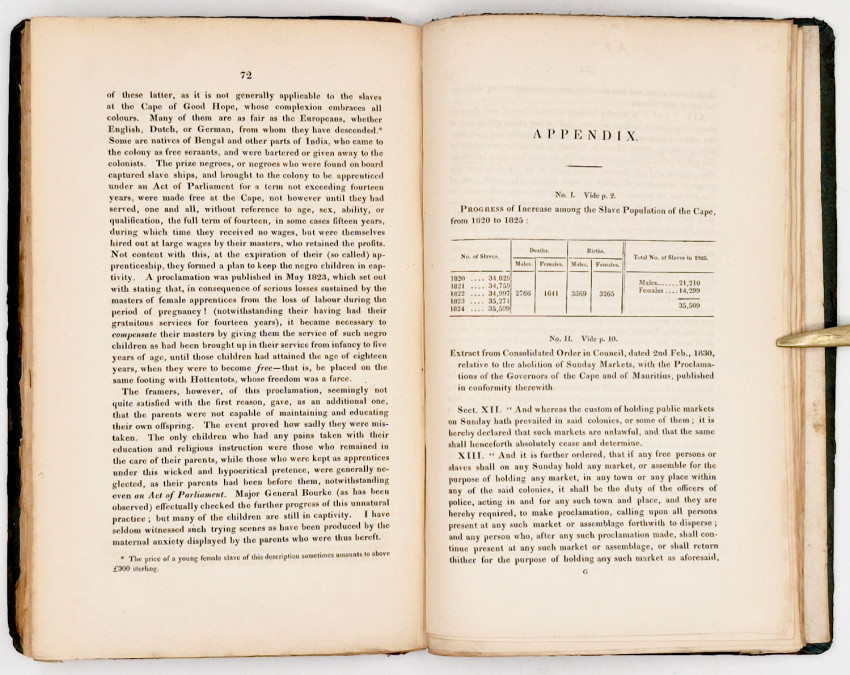

First Edition: vi + 107 pages, original blue paper over boards rebacked with matching paper, a very good copy.

Mendelssohn (Sydney) South African Biography, volume II, page 641, 'A comprehensive view of slavery as then existing at the Cape. The Appendix contains reports of various trials for cruelty to slaves on the part of the Colonists.'

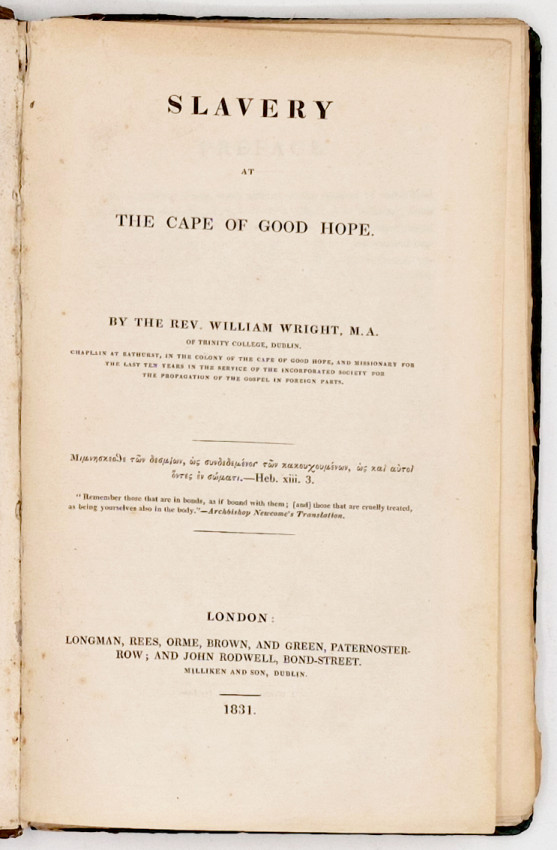

William Wright, D.D., an Irish clergyman, was educated at Trinity College, Dublin, and died in 1856, served at Bathurst in the Eastern Cape as a chaplain. He was interested in the laws, ordinances, and condition of enslaved people in the Cape, from the theological, moral and legal perspectives.

Appendix No. III, Trial of Coenrad Hendrik Laubscher (From the South African Commercial Advertiser of May 26rh 1830). Cruel Treatment of a Slave. Rex versus Laudscher, pages 79-89:

"The Slaves Must Be Heard:" Thomas Pringle and the Dialogue of South African Servitude by A.E. Voss English in Africa Volume 17, Issue 1 May 1990: ‘Pringle's unqualified attack on Cape slavery is resumed in 1828 by William Wright.......Wright's later pamphlet, Slavery at the Cape o/Good Hope (1831), is a polemical documentary, complete with statistical apparatus, but narrative is still central to its argument. Not concerned with "the condition of the slave comparatively with others of his class, but in reference to the great family of man". Wright undertakes to demonstrate the evil principle of slavery," confining his observations principally to the most prominent features and effects of the late legislative enactments, as they respect the Cape Colony". Wright's sequence reaches a climax in the section on trials by jury. One third of his text is devoted to this "most important part" of his subject, and this rhetorical centrepiece reveals in reports of slave testimony "instances of cruelty which have disgraced the country". His first and most striking case is one of "peculiar atrocity," in which Coenraad Hendrik Laubscher is found guilty of assault on the slave Lodewyk. In 1827 Lodewyk had been found guilty of assault on Laubscher, then his master; sentence of death had been reversed on appeal. Wright quotes the Guardian's report of this process, before going on to the later (New Order) trial of Laubscher. During his imprisonment, Lodewyk had been sold "under the express stipulation that he should never be allowed again to visit his wife and children, who were still slaves of Laubscher". Three years later, when Lodewyk has returned to Laubscher's place to see his wife and children, he is apprehended and beaten. Wright has promised "little more than a dry narrative of acts"; but his account of Laubscher's trial spices reportage by, for example, imputing motivation to the accused: "It appears that he had been meditating deep and fearful vengeance"; and by characterization: "the witness, Weise [Laubscher's steward] appears to have been a humane man". Ironically, however, it is in the South African Commercial Advertiser's report, which Wright includes as an Appendix, that the image of the slave approaches Lodewyk as subject most nearly, from the uniformity of tone across the different witnesses induced by translation into English. We learn the details of Lodewyk hiding "among some reeds, and afterwards among sheaves of corn". The slave's account of his own suffering recalls Mayhew's interviews in London Labour and the London Poor, twenty years later; 'He struck me very hard, and when he had ceased beating me he pushed the end of the cane into my mouth and broke two of my teeth, and wounded my upper lip. My teeth were quite sound and perfect before .... My master was not at home when we arrived at his place, but ... his overseer, received me, and washed my wounds and bruises withbukok vinegar; but I was not able to work at my trade, as a tailor, for twenty-two days, in consequence, chiefly, of the state of my right arm. There was blood on the ground under the spot where I sat.' We have learnt, almost in passing, that Lodewyk is a tailor, which suggests that he is a Malay, and perhaps "let out on hire ... or permitted to hire himself ... provided he bring home every night, to his master ... a certain stipulated sum of money", i.e. "Koeliegeld." Is there not in Lodewyk’s economic bondage and physical suffering, prefiguration of Schreiner's Waldo, Peter Abrahams's Xuma, Coetzee's magistrate, Wessel Ebersohn's Bhengu and Douglas Reid Skinner's "The Body is a Country of Joy and of Pain"?'

Book plate of John Edward Walsh, Q.C.L.L.D. on the front paste down endpaper. Walsh (1816-1869), Irish lawyer, judge, and author.

- Overall Condition: Very good

- Size: 8vo (233 x 150mm)