With Portrait, Maps and Illustrations

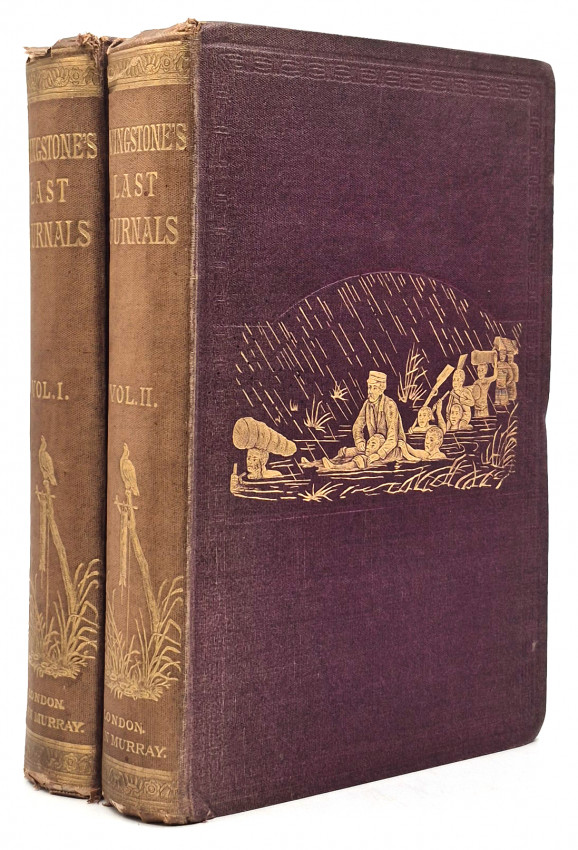

First Edition: 2 volumes, I. 360, II. 346, (vi publisher’s catalogue dated December 1874) pages, frontispiece portrait of Livingstone in volume 1, engraved frontispiece in volume 2, large colour folding map in pocket in back cover of vol. I, 1 other colour folding map, 19 plates, 24 illustrations in the text, original maroon cloth with gilt vignettes on the upper covers and gilt titling and decoration on the spines – the spine are faded, edges uncut, contents crisp, front hinge of volume I split but holding on the ties, back hinge detached caused by weight of the large folding map, bookplate on each front paste-down endpaper, a very good set.

Mendelssohn (Sydney) South African Bibliography, volume 1, pages 912/13,’These journals include "a series of travels and scientific geographical records of the most extraordinary character ... of seven years' continuous work and new discovery, "in the course of which" no break whatever occurs . . . from the time of Livingstone's departure from Zanzibar in the beginning of 1866 to the day when his note-book dropped from his hand in the village of Ilala at the end of April 1873."The objects of the expedition were the suppression of slavery, and the exploration of the South Central Lake system of South Africa, and, with regard to the former, Dr. Livingstone appears to have been greatly distressed at the fearful cruelties of the slave dealers, and the sufferings of the helpless captives are stated to have been of the most awful character. It is observed that "Children for a time would keep up with wonderful endurance, but it happened sometimes that the sound of dancing and the merry tinkle of the small drums would fall on their ears in passing near to a village ; then the memory of home and happy days proved too much for them ; they cried and sobbed, the ' broken heart ' came on, and they rapidly sank." At last Livingstone escaped from the scene of these atrocities, and succeeded in starting for Ujiji, where he arrived on October 23, 1871. Five days later he gained new life and courage by the welcome and unexpected arrival of H. M. Stanley with supplies and letters, and the latest news from Europe. He soon regained his energy, and was shortly afterwards busied with Stanley in the exploration of Lake Tanganyika, at the northern extremity. The latter tried to persuade him to return to England and recuperate and then come back and finish his work, but the undaunted explorer decided to go on, and Stanley left on March 14, 1872, taking Livingstone's despatches and journal to Europe. The last explorations were conducted in the vicinity of Lake Bangwelo, where, thoroughly broken down and worn out, the greatest traveller of modern times died on April 1, 1873, at Chitambo. His faithful servants, Susi, Chuma, and Jacob Wainwright, preserved his body and papers, and brought them safely to England, where his remains were interred in Westminster Abbey, on April 18, 1874.

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (https://www.oxforddnb.com/display/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-16803?rskey=TBl7Eq&result=2)

‘…….Stanley had, of course, taken the lead in reviving Livingstone's celebrity and his book, How I Found Livingstone (1872), presented the traveller as a genial saint. Horace Waller, who had been with the UMCA at Magomero, fastidiously edited Livingstone's Last Journals (1874), a poignant testimony to soul-searching, suffering, forbearance, and tenacity. These books, and their derivatives, contributed to a Livingstone legend which had begun with Missionary Travels. There was a peculiar romance about the lone missionary ever pressing into new country, concerned not to convert but to bear Christian witness by preaching the gospel, giving magic-lantern shows, and speaking against slavery. Livingstone became a symbol of what the British—and other Europeans—wished to believe about their motives as they took over tropical Africa in the late nineteenth century: in effect he redeemed the colonial project. In 1929 the Scottish national memorial to David Livingstone was opened at his birthplace, Blantyre, by the duchess of York; by 1963 there had been 2 million visitors. In Africa, he is still commemorated in the names of two towns: Blantyre, in Malawi, and Livingstone, in Zambia, beside the Victoria Falls.

‘For half a century after his death Livingstone was the subject of hagiography rather than scholarship. More realistic assessments became possible with access to the papers of Kirk and other members of the Zambezi expedition. The chief work of reappraisal, however, was achieved in Isaac Schapera's magisterial editions of Livingstone's journals and letters up to 1856. During the later twentieth century a complex character came into focus: versatile in practical skills, intellectually curious, strikingly free from religious or racial prejudice, exerting unusual charm, and inspiring at least a few to great loyalty; yet deficient in political sense, tactless, touchy, rancorous, stingy with thanks or encouragement, devious, and callous when other people's interests seemed to conflict with his duty to God. Livingstone's reputation for managing Africans, if not Europeans, rests on the expeditions of 1853–6, which were organized chiefly by Africans, and on Waller's emollient edition of his last journals. None the less, his writings have acquired new value as a rich source for the history of Africans. His pioneering cartography of eastern Angola and what became Botswana, Zambia, and Malawi was but one facet of his skill as an amateur field-scientist in an age of growing specialization. Secular knowledge and material mastery were integral to his missiology: the industrial revolution was part of a divine plan. Livingstone both embodied and transcended the nineteenth-century tension between religion and science, and it was this which accounted for the scale and complexity of his career in Africa.’

- Overall Condition: Very good

- Size: 8vo (230 x 150 mm)